UK politics

fromwww.npr.org

1 week agoFormer UK ambassador to the US arrested on suspicion of misconduct over Epstein ties

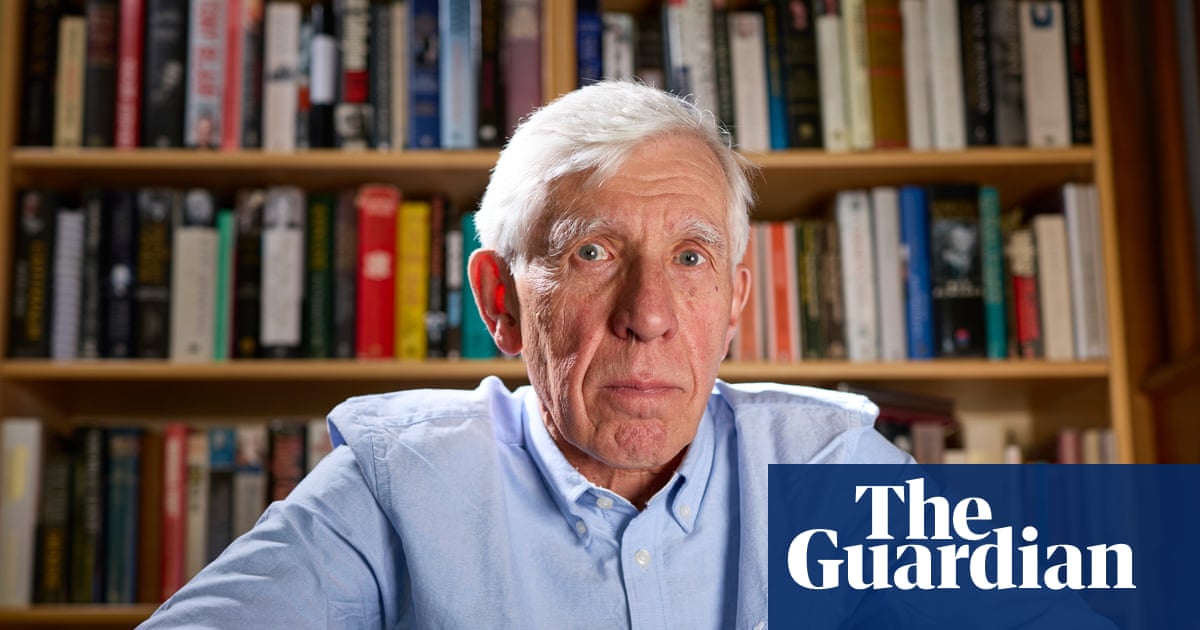

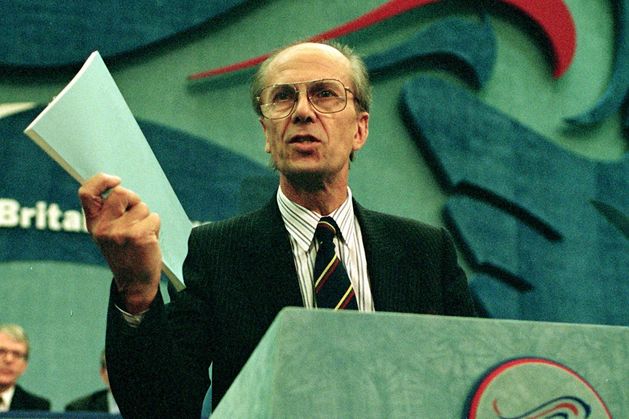

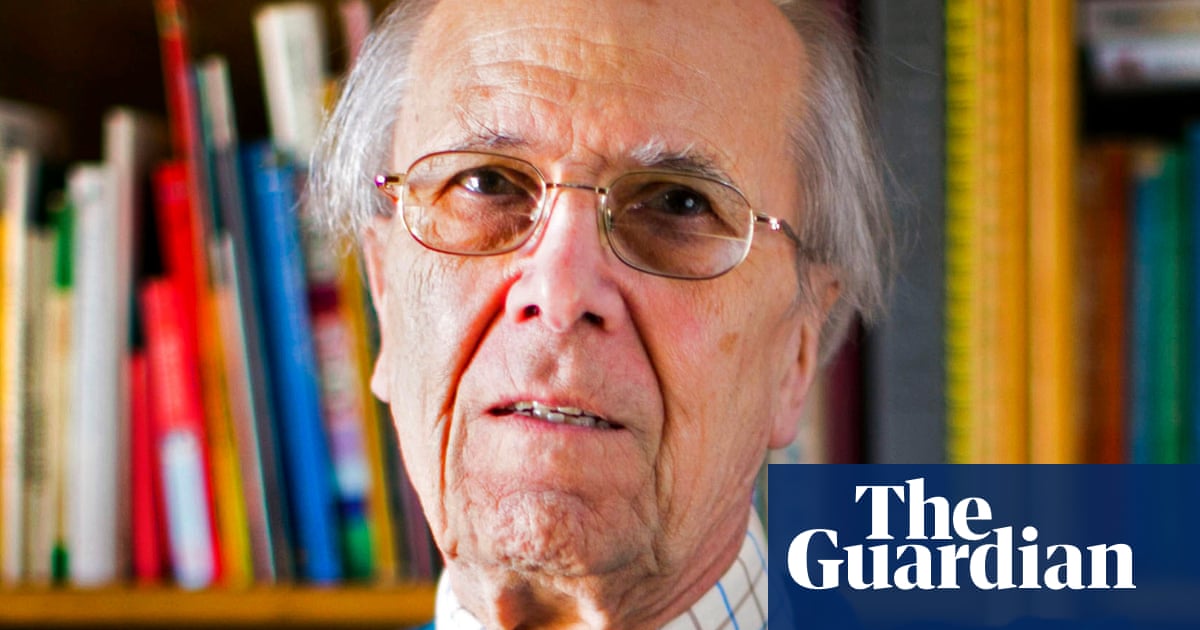

Peter Mandelson, former British ambassador to the U.S., was arrested and accused of passing confidential government information to Jeffrey Epstein, facing potential espionage charges.